Winemakers and sommeliers can use a number of terms to describe how wine tastes, which can often appear confusing and difficult for the average consumer to understand.

In order to simplify this process down, it is generally understood that all wine can be described in terms of four main flavour attributes:

Some flavour attributes, however, are completely unique to certain types of wine, with red wines also being defined on how pronounced their tannins and level of spice are, or sparkling wines receiving classifications on their degree of carbonation.

Whilst these by no means represent the only profiles used in describing the taste of wine, these are simple and easy to understand ways for everyone to compare wine types and discover the wine style that they are most likely to enjoy.

To explore other ways or methods that can be used to describe taste in wine, check out this useful article.

Body in wine is used to describe the texture and weight of the liquid in your glass as it enters your mouth.

The way we perceive body in wine is heavily affected through the sweetness of the wine, its alcohol content, its prevailing acidity, and, in the case of red wine, how pronounced its tannins are, with our taste receptors registering different mouthfeels depending on each of these attributes.

In addition to this and exclusive to sparkling wines, the level of carbonation is a strong determining factor in a wines body. For a quick reference on how body in wine is influenced, refer to our guide below.

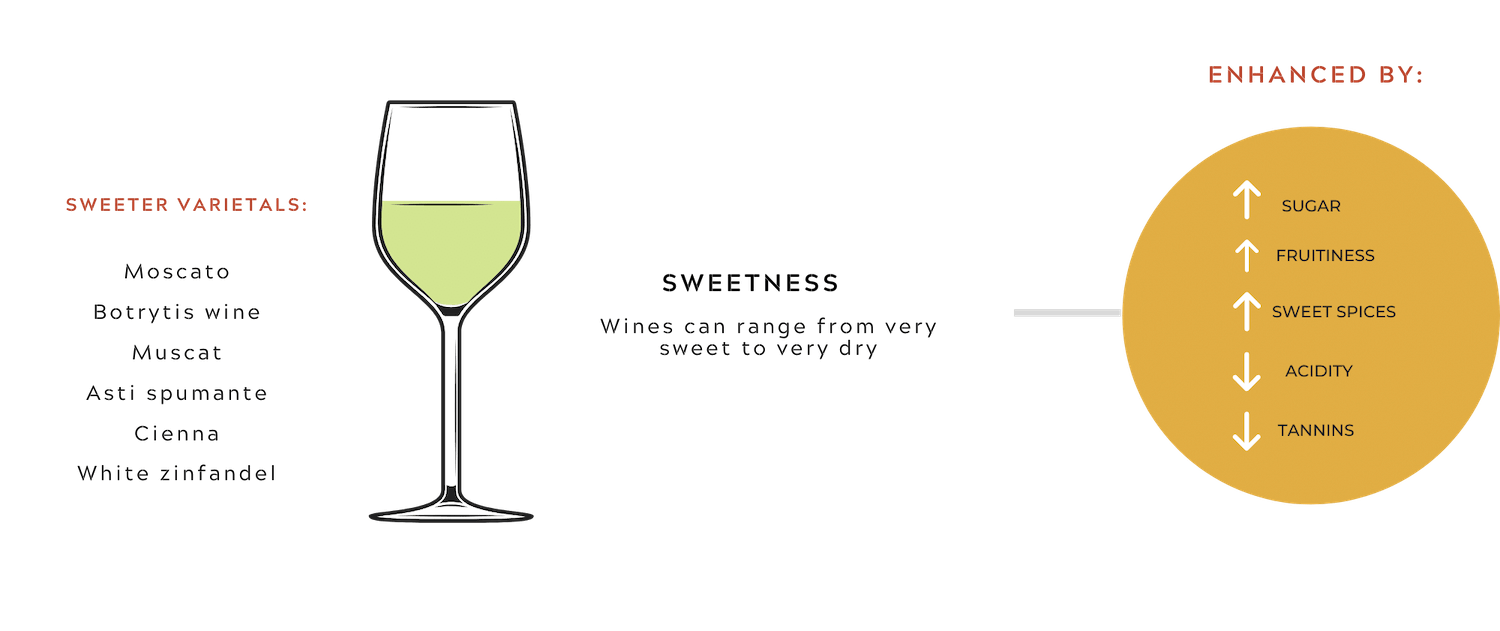

During production, most of the sugar in wine is consumed by the yeast, producing alcohol, with whatever amount remaining afterwards being called the residual sugar.

Whilst most would assume that higher amounts of residual sugar would always result in sweeter wines, this isn’t always the case as wines that have higher levels of tannin or acidity will taste less sweet, even when comparing two bottles with the same amount of sugar.

It’s also possible that wines may taste sweeter than their residual sugar levels might otherwise indicate due to a strong presence of fruit or sweet spice flavours, which can make them taste sweet.

Keeping this in mind, it is often best to classify wines based on how sweet, or dry, they actually taste, with all attributes and flavours considered, rather than focusing solely on their residual sugar levels, as doing so results in a more accurate description of the sweetness in the wine being tasted.

For a simple guide on the sweetness levels described in wine, see below.

Though acidity might not be to everyone's taste, in wine it plays a crucial role in helping to protect it from developing faults and going off.

In general, wines that are higher in acidity are more light-bodied than their lower acidity counterparts and if the wine is too acidic or not acidic enough, it can taste either flat and dull, in the case of the former, or sharp and sour, in the case of the latter.

When done right, however, acidity can impart positive flavours of tartness, freshness, and zest, which make our mouths salivate and desire more of the wine we’re drinking.

Though it is present in all wine types, acidity is usually described a little differently when tasting a white or sparkling wine versus a red wine. In white and sparkling wines, those with higher levels of acidity are often described as being crisp, as this word has better connotations than acidity.

In red wines, however, it is more common to simply describe it on a scale of highly acidic to not at all. Going back to all wine, it’s also important to note that a wine that has been described as high in acidity or crispiness can still contain strong levels of fruitiness, as these are two distinct flavour attributes that are not mutually exclusive.

You’ll often hear sommeliers and winemakers describing wine based upon the various fruit or other flavours present within a bottle.

Whilst this might lead some to believe that those fruits or flavourings were used in the production of the wine in question, this isn’t the case, with grapes being primarily responsible for the majority of fruit-like flavours found in wine and oak ageing being reponsible for most of the tertiary, or secondary, flavours described.

The reason why we taste different types of fruit in wine is because grapes naturally, and especially during the fermentation process, release many of the same chemical properties that can be found in other fruits.

The specific fruit flavours we taste in wine will also vary greatly depending upon the type of wine being sampled, as dark berries and red fruits are commonly found in red wines, whilst citrus and stone fruits, such as lemons, pears, or peaches, can often be found in white wines.

Depending upon the strength of these fruit flavours, you can describe a wine as being heavily fruit-forward or fruity, or low and subtle in its fruit characters.

Other than fruit flavours, it's also possible to discover many other tertiary or secondary flavours outside of fruits within a particular glass, such as sweet or dry spices or even notes of butter or cream, which are often signs that the wine has been aged in oak.

Taking all of the prominent fruit or other flavours into consideration helps to explain why some wines will be considered or described, particularly by non-experts, as sweet even though the wine itself actually has a low sugar content.

To give you a perfect example of this, consider a heavily oaked and buttery style of chardonnay, such as many of those coming from California.

These wines are notoriously buttery and creamy in their taste and full of ripe tropical fruit flavours, such as pineapple, mango, or melon, and sweet spices, including vanilla, which makes them taste sweet even though the actual sugar content of the wine is low.

It is for this reason that, whilst professionals, such as sommeliers, will seperate the flavours of a wine from its level of sweetness, which is often only described in terms of its sugar content, it is recommended, particularly in a sales situation or when describing wines to an average drinker, to consider the entire flavour profile of a wine when deciding whether or not it tastes sweet or dry.

Tannins are easily the most misunderstood attributes of red wines, with them directly influencing not only a wines body but also how dry it tastes.

Without going into the science behind what tannins are, they can simply be described as naturally occurring compounds that are released from all parts of the grape during production, including the skin, stem, and seeds.

The presence of tannins typically imparts a drying and bitter sensation in your mouth, with a noticeable grittiness occurring on your teeth the greater its presence.

Whilst the taste of tannins in wine is typically strongest when they’re young, with this softening or reducing as the wine is allowed to age for longer, the wine can also gain tannin from ageing in oak, however the effect from oak tannin is less noticeable.

Other factors affecting how much tannin goes into the wine also include the grape varietal used to produce the wine, as some naturally produce more, and how long the skin, stem, and seeds of the grapes are allowed to rest with the juice during production, as the longer it sits, the more tannins are imparted.

Another flavour attribute that is often attributable to many red wines is the wines inherent type and intensity of spice, which is a noticeable heat or tingle that is felt once the wine is consumed.

Some of the specific spice flavours present in wines are often compared to pepper, cinnamon, anise, or mint, to name a few, with different grapes and ageing techniques producing varying spicy characters and levels of intensity.

As is the case with fruit flavours present in wines, these spicy characteristics are not present because of the use or presence of this particular spice during production but from the chemical properties produced during a grapes fermentation or from the barrels used to age the wine.

Whilst describing the particular spicy flavour that is being felt in a particular wine can be very difficult, it is often much easier to describe the intensity of the spice being felt, with some wines possessing none at all and others containing overwhelming amounts of spice.

Sparkling wines and Champagnes are unique in that they contain some amount of carbonation, or bubbles, that can greatly influence how a person perceives the flavour, and particularly the body, of the wine.

How these wines are produced plays a strong role in the level of carbonation in the resulting wine with it often being said that Champagnes and other sparkling wines made in the traditional style possess finer bubbles than those made in other fashions, including the more widely used tank carbonation method.

As mentioned previously, highly carbonated wines tend to feel lighter than their less carbonated counterparts, and the more aggressive the bubbles are, the less elegant the bottle of wine is typically considered.

Though not one of the most important flavour attributes in wines, alcohol still plays a direct role in how we perceive the body of the wine as well as how much bitterness we taste.

As mentioned previously, during the fermentation process, the sugars present in the grape is consumed by the yeast, which produces alcohol.

Depending upon how much sugar is present in the grape to begin with, and how long it is fermented for, the alcohol content of the resulting wine will be different as grapes with lower sugar, or those that are fermented for less time, will produce a lower alcohol level.

In addition to affecting the body of the wine at higher levels by making the wine feel fuller-bodied, it is common for wines, and alcoholic drinks in general, to taste more bitter in taste at higher alcohol levels.

In fortified wine, which is made differently to normal wine, brandy is typically added at some point during the production process, which serves to increase the alcohol levels in the wine and add to the existing flavour profile.

It’s not uncommon to hear sommeliers describe a particular bottle of wine as “easy-drinking” or “smooth”, which, though a trait generally appealing to average consumers, is a terrifying distinction for many winemakers to earn.

The negative connotations that exist around smoothness, or how easy the wine is to drink, mainly relate to the fact that easy drinking wines are often perceived as being flavourless, boring, dull, or not particularly special, all traits not associated with a high quality or award winning wine.

That being said, many winemakers and, in particular large brands, often make it a point to produce wines without any intense flavours or characteristics, so as to make wines that are appealing to as large an audience as possible.

For a general guide, wines that sit at the extreme end of tannins, spiciness, acidity, carbonation, or dryness, tend to not be very smooth in their nature, with it far more likely to find a smooth wine as being more moderate and decidedly average in overall character.

Varying in its tastes, colours, and serving suggestions, white wine has a well deserved place as one of the most popular types of wine. Review our guide to white to find out not only what the prominent white wine varieties are but also how each one tastes and how to pick one suited to you.

Served prominently in times of celebration and fun, bottles of sparkling wine can be some of the most expensive and premium examples of wines available anywhere. Our guide to sparkling wine will share with you all that you need to know about this wine type, including its popular styles and tastes.

Easily some of the best wines to consume when the weather is hot and the sun is out, rosé wines vary in their flavour profiles and ideal consumption patterns. In our guide to rosé we help enlighten you as to the prominent styles that exist in this type of wine and explore common serving suggestions.

Varying immensely in its flavours and production methods, fortified and dessert wines are often overlooked and misunderstood. In our guide to fortified and dessert wines, we go into detail about many of the different styles in this category and how to effectively pick the right bottle for you.